From Symptom-Driven Innovation to Causal Change in Business and Society.

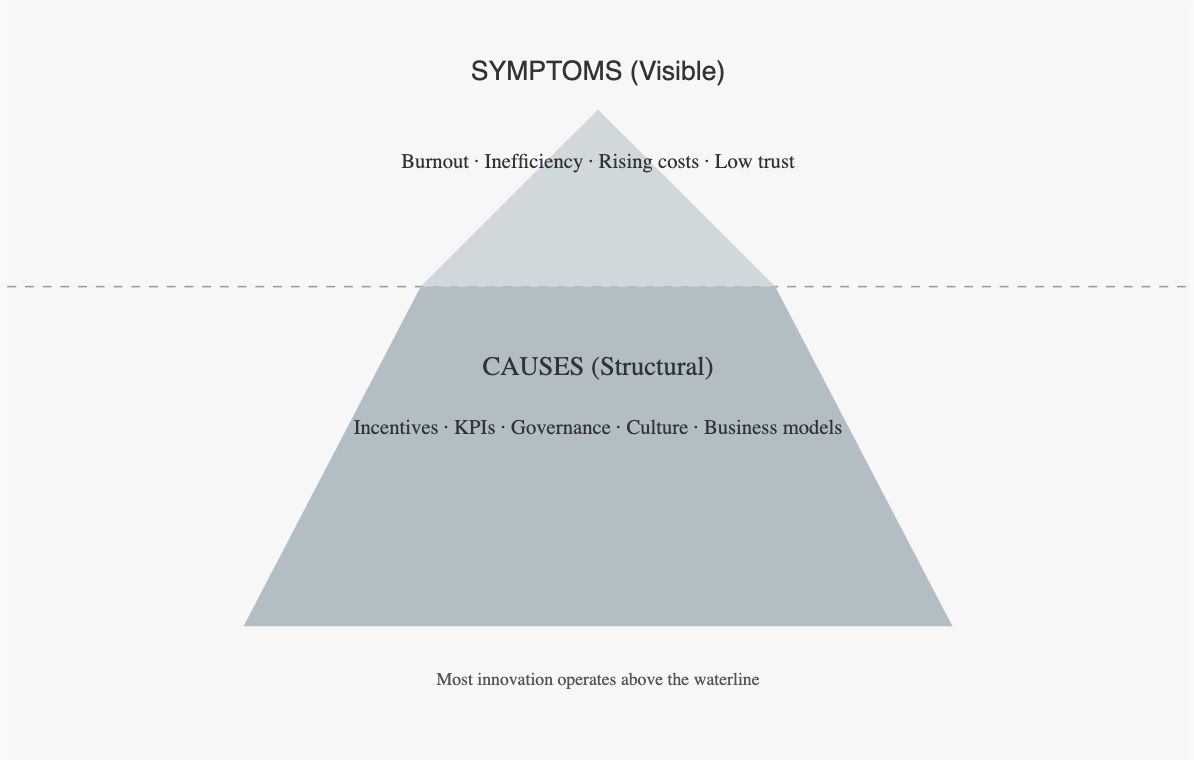

Innovation has never been more visible. Yet despite unprecedented investment in transformation programmes, design methods and purpose-driven strategies, the same organisational and societal problems keep resurfacing. Burnout is addressed without changing how work is organised; sustainability is pursued without shifting growth logic; innovation accelerates while impact plateaus.

This raises a more unsettling question: what if much of today’s innovation is not failing but succeeding at the wrong level, easing symptoms while leaving their causes intact?

BY MIKHAEL AKASHA

“We are fixing appearances, not structures. ”

Across business and society, there is clear momentum behind efforts to challenge the status quo: new ventures, public-sector transformation programmes, ESG-driven strategy shifts, and the mainstreaming of human-centred approaches to problem solving. This trajectory is encouraging because it signals a willingness to question inherited assumptions and redesign how value is created and distributed.

At the same time, I observe a recurring gap between the ambition to change and the causal depth of the solutions proposed. In many organisations, the dominant pattern remains: intervene where pain is visible; optimise what can be measured quickly; treat immediate symptoms rather than the underlying conditions that generate them. The result can be activity without structural resolution.

This tension marks a critical inflection point in contemporary innovation.

A recurring pattern: visible improvement, persistent recurrence

In organisational settings, symptom-focused responses are common. Teams act where impact can be demonstrated quickly and where interventions fit existing structures. Yet empirical observation shows that many challenges; burnout, declining trust, sustainability trade-offs, digital overload, stalled transformation, reappear over time, often in new forms.

This is not a failure of effort or intelligence. It reflects a structural bias toward downstream intervention rather than upstream causation. A similar bias has long been documented in Western medical healthcare for example.

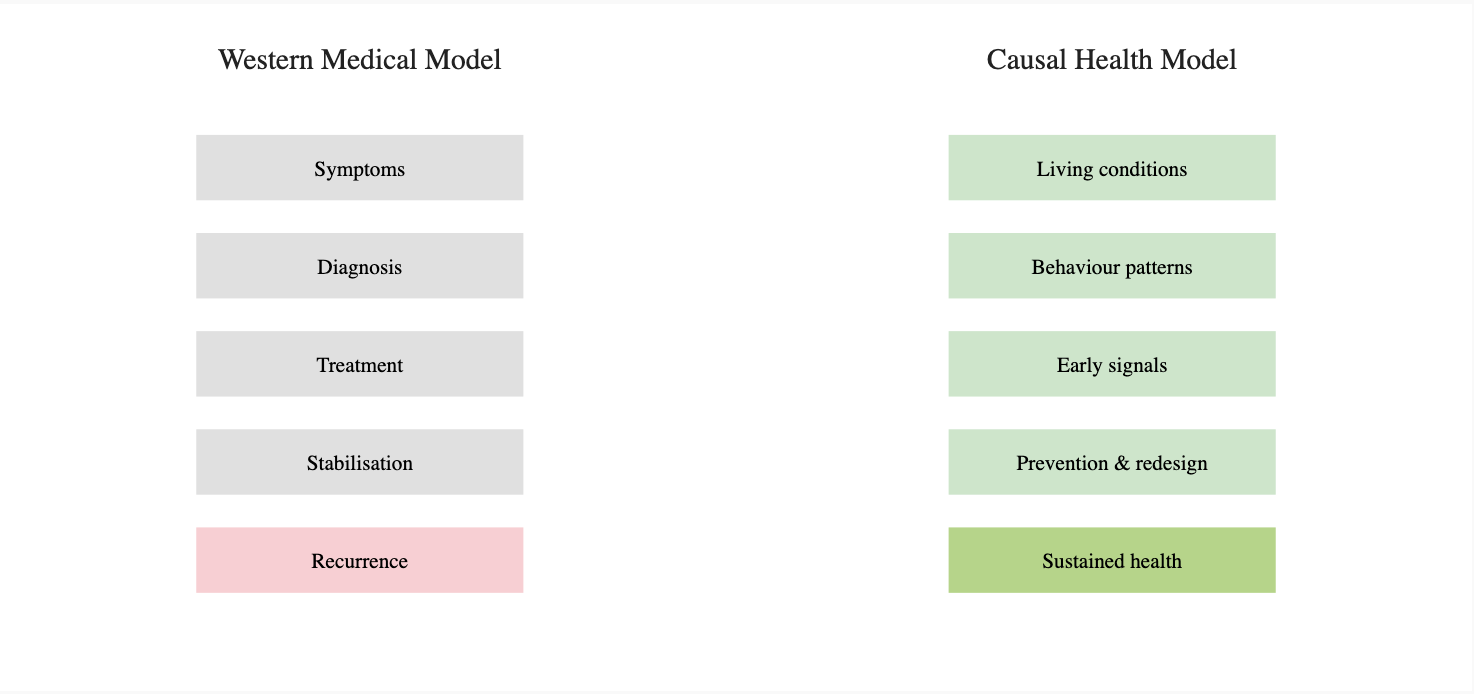

Western medicine and the structural focus on symptoms

The prevailing medical paradigm in most Western countries is the biomedical model. It conceptualises illness primarily as a biological dysfunction that can be diagnosed and treated through targeted clinical intervention.

However, when examined at the system level, Western healthcare shows a strong emphasis on treating symptoms once disease has manifested, rather than on addressing the conditions that cause illness over time.

The data demonstrates this:

In the European Union, preventive healthcare represents only a small share of total health expenditure, while the vast majority of spending is allocated to curative care, long-term disease management, and clinical treatment of established conditions.

In the United States, approximately 50% of adults live with at least one chronic condition, and chronic diseases account for over 85–90% of total healthcare spending. These conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and stress-related disorders are strongly linked to behavioural, environmental, and socio-economic factors that emerge long before clinical intervention occurs.

In other words, Western medical systems are structurally optimised to fight symptoms: reduce pain, stabilise disease, manage risk and prolong functioning. They are far less optimised to redesign the upstream conditions; lifestyle patterns, work environments, social stressors and environmental exposures that generate illness in the first place.

This does not diminish the life-saving achievements of modern medicine. It highlights a structural imbalance: a system designed primarily for intervention rather than prevention will inevitably reproduce high levels of chronic burden.

Innovation shows the same pattern: fast fixes, persistent recurrence

In organisational innovation, symptom treatment often takes forms such as:

Processes are digitised without questioning the incentive systems that created inefficiency.

Wellbeing programmes are introduced while workload design and leadership behaviour remain unchanged.

Customer experience is improved at the interface level while the underlying business model continues to generate friction.

Sustainability initiatives are launched as parallel projects rather than integrated into core strategy and decision-making.

These actions often deliver measurable short-term benefits. Yet when root causes remain untouched, the same issues tend to recur. Sometimes with increased complexity and cost.

Where Design Thinking helps and where it can fall short

In my lectures and innovation project work at Maastricht University, Design Thinking is a method for innovation to solve complex problems. Its strengths are well documented: structured empathy, iterative learning, rapid prototyping and cross-disciplinary collaboration. Research on design maturity consistently shows that organisations with more advanced design capabilities tend to perform better on innovation outcomes.

However, Design Thinking can unintentionally reinforce symptom-level innovation when it is applied primarily as a solution-generation engine. Teams may become highly effective at producing better solutions while insufficiently interrogating whether they are addressing the right level of causality.

Without deeper framing, Design Thinking risks accelerating responses to problems that are themselves poorly understood.

Moving toward causal, holistic innovation

A more mature approach to innovation expands beyond immediate problem-solving and incorporates additional layers of inquiry:

Systems thinking, to make feedback loops, incentives, and dependencies visible.

Problem framing as a core intervention, recognising that how a problem is defined shapes all downstream solutions.

Explicit causal hypotheses, clarifying why an intervention is expected to work and under what conditions it might fail.

Integration of behavioural, social, and structural evidence, not only user insights or market signals.

These elements do not replace existing tools; they deepen them. They shift innovation from reactive optimisation toward intentional system redesign.

Why maturity and time matter

Causal innovation is inherently more demanding. It requires tolerance for ambiguity, willingness to question entrenched assumptions and the capacity to work with delayed outcomes. Causes are rarely located in a single place; they are distributed across governance structures, incentive systems, cultural norms, and power relations.

This is why symptom-focused approaches remain dominant: they are faster, easier to measure and less disruptive. Yet when the goal is durable transformation, rather than incremental improvement, causal depth becomes essential.

Conclusion and invitation

The current wave of innovation reflects a genuine shift in awareness and intent. That shift becomes consequential only when it moves beyond treating visible problems and begins to engage with the conditions that generate them. Just as healthcare systems are increasingly challenged to move from managing illness to creating health, innovation systems are challenged to move from surface-level solutions to structural change.

If this perspective resonates with you, or if it triggers discomfort or recognition, it may be pointing to a deeper question about where your organisation, project, or leadership practice is currently intervening.

If you feel drawn to explore this further, you are welcome to reach out for a conversation. Sometimes the most meaningful innovation begins not with a solution, but with the courage to examine causes together.

About the Author

Mikhaël Akasha is a transformational leader working at the intersection of systemic strategy, life-serving innovation, and human development. As founder of Human by Design and as Innovation Lead and Lecturer at Maastricht University, he supports organisations in translating purpose into practical strategy, applied innovation, and learning journeys that endure over time.

Bridging decades of work with global organisations, academic leadership programmes, and ancient wisdom traditions, his work invites leaders to let clarity within shape conscious action and to design innovation that truly serves life.